|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A BRIEF HISTORY OF GRASSROOTS GREENING IN NYC by Sarah Ferguson In the Fall of 1748, Peter Kalm, a Swedish naturalist, visited New York City to catalog the local flora and fauna. "I found it exceedingly pleasant to walk in the town for it seemed quite like a garden," Kalm wrote. "The trees which are planted for this purpose are chiefly of two kinds, the Water Beech... are the most numerous... and the Locust... Likewise lime trees and elms but they are not by far so frequent. Tree frogs... are so loud it is difficult for a man to make himself heard. Homes [are] shingled with White Fir Tree."(1) Kalm's bucolic vision of Manhattan was soon to be plowed over by the imposition of the grid-iron street pattern in 1811. Yet even today, an observer passing through the streets of the Lower East Side can still capture some inkling of the natural wonder that once was. Start early in the morning at the Hua Mei Bird Garden, a patch of green carved out of the cracked asphalt of Sara D. Roosevelt Park between Forsyth and Chrystie Streets, where Chinese men come to air their canaries, finches, and golden-brown Hua Mei (literally, beautiful eyebrow) birds in delicately carved bamboo cages suspended from wrought-iron perches. Fellow members of the Forsyth Gardening Club have studded the neighboring trees with colorful birdhouses, home to numerous sparrows, crows, starlings, and bluejays whose cacophonous twitters and shrieks cascade through the park, all but drowning out the rush-hour traffic. Make your way east through the congested streets south of Houston, where Puerto Rican and Dominican gardeners have turfed out small casita gardens on stray lots, filled with domino tables, homemade shrines, and vegetable plots lined with plastic coca-cola containers. A few blocks north at the 6th and B Garden, Edie's Watts-like tower of plywood, stuffed animals and plastic figurines rises from an eclectic patchwork of plots brimming with fruit trees, flowers and veggies. Half a block east at the 6BC Botanical Center, gardeners have relandscaped the gritty city earth into a meandering oasis, replete with a grape arbor, a koi pond fed by a miniature, solar-powered waterfall, cactus and Japanese rock gardens, a "chinoiserie" teahouse, and a recessed grotto devoted to northeastern woodland flora. Two blocks south, Parque de Tranquilidad conjures the overgrown, lush feel of an English garden, with tiled bird baths and winding stone pathways lined with holly, birch and dogwood. By contrast, the oversized brick barbecue in Green Oasis on 8th Street and Avenue C looks like something out of an old Italian village. During the Fiesta de Cruz in June, Puerto Rican women can be found singing fervent hymns of devotion in the rose-covered gazebo as fully veiled Muslim women and their children amble on the lawn. Next door, Albert's Garden is filled with carved African totems, the legacy of Albert Eisenlau, a sculptor who died in 1999. Many of these community-tended spaces have evolved into teaching programs for local children, like the LES Garden on 11th Street, next door to Junior High School 60. Once a toxic wasteland--contaminated with propane and heavy metals after the city demolished an old bus garage--the garden now boasts a compost-heated greenhouse, startlingly verdant, organic lawns, a goldfish pond, and bird and butterfly habitats. At sundown, you can hear peals of laughter from neighborhood kids gathered for potluck suppers oscillating with the sound of the imam intoning evening prayers from the steps of the mosque next door. And on warm, weekend nights, slip over to the 4th Street Casita garden, whose front porch is generally packed with musicians performing traditional plena, bomba, and meringue, their plates brimming with arroz con pollo. This quite brief sampling of the roughly 50 community gardens still thriving on the Lower East Side is testament to the tenacity of this former immigrant haven, which has clung to its small-scale, village charm far longer than anyone would expect for a neighborhood situated within such a short commute to Wall Street. Collectively, these green havens are like an urban rainforest of cultural diversity and social expression whose beauty and ingenuity grow all the more precious as their margins are encroached by gentrification.

By contrast, the eclectic patchwork of more than 800 community gardens that have taken root in New York since the 1970s were born not out of government support, but rather its neglect. During the fiscal crisis, waves of arson and abandonment left the city scarred with thousands of crumbling buildings and vacant, rubble-strewn lots. By 1977, there were more than 25,000 vacant lots in New York.(4) Littered with trash and rats, these open sores became magnets for drugs, prostitution, and chop shops for stripping down stolen cars. Yet the city's only response was to spend thousands of dollars enclosing the lots with cyclone fencing. Fed up with government inaction, in 1973 an impassioned artist named Liz Christy and a band of like-minded activists called the Green Guerrillas began taking over abandoned lots on Manhattan's Lower East Side. Armed with bolt-cutters and pickaxes, they conceived of themselves as a strike force to liberate the crumbling landscape around them. They founded their first garden on the corner of Bowery and Houston, where a few months earlier a couple of bums had been found frozen to death in a cardboard box. "You could not have picked a more unlikely place to start a garden," recalls Bill Brunson, an early Guerrilla. "At the time, there were still all these men lined up along the Bowery drinking wine and panhandling. To put a garden there--in what was probably the ultimate slime spot in the city--that was unheard of." It was also, in the eyes of bureaucrats, illegal. At first the City accused the group of trespassing and threatened to boot them off the land. But after a media blitz, when the Guerrillas brought in TV cameras to show how they transformed the lot--creating soil with nothing but sifted rubble and compost--the City backed down and offered them a lease in 1974. (5) The Liz Christy garden, as it later became known, was a lightning rod for do-it-yourself greening, inspiring passersby to create similar plots in their own neighborhoods. The Guerrillas held training sessions and set up a phone line so people could call to find out where to get free plants and trees. They also lobbed 'seed Green-Aids'--balloons or Christmas-tree ornaments stuffed with peat moss and wildflower seeds--into fenced-off lots and along highways across the five boroughs. "It was a form of civil disobedience.," recalls Amis Taylor, another early GG member. "We were basically saying to the government, if you won't do it, we will." By 1976, their efforts were beginning to win over government officials, including Brooklyn Congressman Fred Richmond, who pushed through a federal program to support urban gardening. In Brooklyn, the first demonstration project was set up through Cornell University's Cooperative Extension Service. It was so successful that a national program was funded at $3 million and expanded to include 15 other cities. Appalled by the devastation he witnessed during his historic walk through the burnt-out sections of the South Bronx, in 1977 Jimmy Carter pledged $500,000 for new parks and recreation facilities, part of a $10 million proposal for immediate aid to the area. That proposal eventually led to the allocation of $1.2 million in federal and New York State funds for community garden and parks development in the South Bronx. The grant required a 50 percent match of local funds--monies the bankrupt city government could ill afford. So, in one of the first official recognitions of the value of sweat equity, gardeners tallied up their volunteer hours--as well as the bricks, beams, and fallen telephone poles they'd recycled from their devastated community, and even the compost they generated--in order to come up with $300,000. The city made up the remaining $900,000 through street trees and sidewalk improvements. The gardens became catalysts for community development."Once people succeeded with the garden, they went on to other things like fixing the schools, housing, creating jobs, whatever was needed," says Taylor. In the Bronx, some of the community groups that emerged through the early greening schemes include the Bronx Frontier Development Corp., the Institute for Local Self Reliance, and the People's Development Corp.(6) On the Lower East Side, gardens grew in tandem with the burgeoning homesteading movement. In the early '70s, a former Civil Rights activist from the South named Sarah Farley formed a group called LAND (Local Action for Neighborhood Development) aimed at creating self-help housing and open space. "Sarah told us, do the gardens first, then the buildings," recalls David Boyle, who helped found the 6th and B Garden in 1981, as well as a series of squatter homesteads on East 13th Street (five of which were evicted in 1995 and 1996). "The gardens were a natural screening process for who could be good homesteaders," says Boyle. "We figured anyone nutty enough to climb over a fence and start clawing away at the dirt with a hammer would be a good squatter. The gardens also attracted more activist minded people into the neighborhood who appreciated the social fabric they provided." For many of these activists, gardens were seen as part of an overall strategy of urban self-sufficiency. In addition to cleaning up empty lots for gardening, a group called the East 11th Street Movement topped one of their homesteads with a solar greenhouse and the nation's first rooftop windmill generator. They also installed a 300-gallon fish farm in the basement of another squat, stocked with hundreds of tilapia, African fresh-water fish. While the fish farm and windmill were shortlived, the garden they started on East 12th Street went on to become El Sol Brillante, which incorporated as a landtrust in 1978 and is now run by members of the East 12th Street Block Association.(7) With so many gardens cropping up on city-owned land, in 1978 the city established Operation Green Thumb, which leases plots for $1 a year. Gardeners and greening groups had pressured for the program as a way of legitimizing their efforts. "They realized they were squatting and wanted some recognition of their right to be there," says former Green Thumb director Jane Weisman. But others saw it as a bureaucratic means to control the ad-hoc appropriation of abandoned land. From the start, the City made clear that all leases were issued on a "temporary" basis. In order to enter the Green Thumb program, gardeners had to agree to vacate their plots within 30 days if the land was ever selected for development. In 1983, the City began issuing some five and ten-year leases. But property interests remained primary; any gardens occupying land valued at over $20,000 could not receive a long-term lease. By the early 1990s, some 850 gardens had been established--more than 60 of them on

the Lower East Side. Yet these plots were becoming increasingly threatened as the

neighborhood gentrified, and the city revived long-standing development plans.

Through Young's group, Earth Celebrations, gardeners on the Lower East Side began organizing around the concept of creating a neighborhood land-trust. In 1995, they began holding monthly meetings to strategize for longterm preservation. When HPD announced in 1996 that it intended to take back half of the Green Thumb gardens citywide, Young and her fellow activists joined with gardeners from other boroughs to form the New York City Garden Preservation Coalition. On February 13, 1997, they organized the first citywide garden rally. Led by giant puppets, more than 300 gardeners and supporters marched from City Hall Park delivering 'valentines' of flowers and herbs to city officials, along with petitions demanding that the city recognize the validity of their green spaces. The street tactics clashed with non-profit greening groups, including Green Guerrillas and the Trust For Public Land, which had privately taken the position that not all gardens could be saved. Instead, TPL worked with Green Thumb to get the more established gardens preserved as park land. In 1996, the 6th Street and Avenue B garden--a large corner lot known for its bizarre, Watts-like tower of plastic toys and stuffed animals--was granted parks status. Fourteen others gardens have been transferred or are in the process of being transferred to the Parks Department. Among them are the 6th and B Horticultural Center, which features several goldfish ponds, waterfalls, and flora native to New York State; and Green Oasis, which offers a large stage for children is theater, a carp pond, and raised beds for the handicapped. But for every garden saved, it seems, another is sacrificed. Fourteen of the Lower East Side's gardens are to be auctioned this May, and the remainder are endangered, including, ironically enough, the Liz Christy garden. Despite its magnificent plantings, this mother of all community gardens could soon be destroyed, a victim of neighborhood redevelopment. FOOTNOTES

2. Bill Weinberg, "Legacy of Rebellion: Tompkins Square and the Lower East Side," Downtown Magazine, Feb. 14, 1990. 3. H. Patricia Hynes, A Patch of Eden (Chelsea Green Publishing Co., 1996) p. xi; Tom Fox, Ian Koeppel, Susan Kellam, "The Struggle For Open Space" (Neighborhood Open Space Coalition, 1985), pp. 3-6. 4. Mark Francis, Lisa Cashdan, Lynn Paxson, Community Open Spaces(Island Press, 1984) p. 4. 5. Lili Wright, A Labor of Love, Not Just a Garden, The Villager,Nov. 12, 1987; interview with Bill Brunson. 6. Fox, et. al., pp. 16-21 7.John Kalish, "Urban Agriculture is Working in the Middle of Manhattan," The Aquarian, June 25, 1980; Francis, et al., pp.85-97. John K. Originally published in the book Avant Gardening,Autonomedia 1999. |

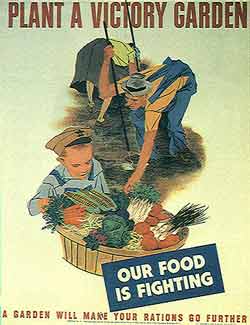

Community gardening in New York

has always followed the boom and bust cycles of the economy, with gardens

sprouting up during periods of stress and falling land values, then withering

away when demands on the land became overwhelming. During the Depression, the

City's welfare department and the federal Works Project Administration sponsored

nearly 5,000 'relief' gardens on vacant and city parks--including Tompkins Square,

where thousands of neighborhood kids were issued 4' -by- 4' plots, and the crop

divided equally at the end of the harvest.(2) But the WPA canceled the relief

project in 1937, when the USDA initiated its food stamp program for farm-surplus

products. Though many immigrant families continued tending backyard plots, the

gardening cause remained dormant until WWII, when the city announced that all

available, city-owned land would be cultivated for Victory Gardens. Despite their

success, these plots were abandoned at the close of the war, when the end of food

rationing and a burgeoning frozen-food industry squelched the initiative of urban

farmers.(3)

Community gardening in New York

has always followed the boom and bust cycles of the economy, with gardens

sprouting up during periods of stress and falling land values, then withering

away when demands on the land became overwhelming. During the Depression, the

City's welfare department and the federal Works Project Administration sponsored

nearly 5,000 'relief' gardens on vacant and city parks--including Tompkins Square,

where thousands of neighborhood kids were issued 4' -by- 4' plots, and the crop

divided equally at the end of the harvest.(2) But the WPA canceled the relief

project in 1937, when the USDA initiated its food stamp program for farm-surplus

products. Though many immigrant families continued tending backyard plots, the

gardening cause remained dormant until WWII, when the city announced that all

available, city-owned land would be cultivated for Victory Gardens. Despite their

success, these plots were abandoned at the close of the war, when the end of food

rationing and a burgeoning frozen-food industry squelched the initiative of urban

farmers.(3) Inspired by the destruction of

Adam Purple's world-renowned Garden of Eden, in 1994 another Lower East Side

woman named Felicia Young began hosting pageants to dramatize the plight of the

area's green spaces. Every spring, throngs of glitter-and-gauze wrapped dancers,

giant puppets, and mud-caked performers wind their way through the neighborhood's

eclectic spaces, re-enacting the gardeners struggle to keep their land.

Inspired by the destruction of

Adam Purple's world-renowned Garden of Eden, in 1994 another Lower East Side

woman named Felicia Young began hosting pageants to dramatize the plight of the

area's green spaces. Every spring, throngs of glitter-and-gauze wrapped dancers,

giant puppets, and mud-caked performers wind their way through the neighborhood's

eclectic spaces, re-enacting the gardeners struggle to keep their land.